Will Qianhai jeopardize Hong Kong’s position?

By Nathan Chow Hung Lai (周洪禮)In mid-2012, the China’s State Council approved the development of the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone.

Four industries were focussed upon: finance, logistics, information services and science & technology services. Particular emphasis was placed on finance, for which the government designated Qianhai to be built into an experimental zone for financial innovation and further opening-up to the outside world.

Back then, market watchers found it difficult to associate the mudflat with such bold plans. We, however, have been optimistic about the project. Specifically, we stated in earlier report that the zone’s development would be kicked off by the launch of a cross-border RMB lending scheme (see “CNH: RMB lending set to cross border in pilot plan”, 16 April 2012).

In Jan13, only nine months after the approval has been granted, fifteen Hong Kong banks were authorized to offer a combined RMB2 bn of loans for Qianhai companies. More impressively, the first Qianhai land auction was held in July and construction is planned to start by October. It signals that the zone has already entered into an expansion period.

An analogy of Shenzhen SEZ in 1980s

While many were previously skeptical about Qianhai’s future, they have now turned to the other extreme of worrying that its rise might jeopardize Hong Kong.

Such fears are overblown. In our view, the Qianhai project is similar to the establishment of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in the 1980s, which has, in fact, bolstered Hong Kong’s competiveness.

Three decades ago, Hong Kong’s manufacturing industry was hit by soaring costs. Factory rents and manufacturing labor wages ballooned 140% and 170% respectively during 1980-90.

The city’s international competiveness was being challenged by several lower-cost developing countries in the region. For instance, the manufacturing labor costs in Indonesia at the time was only one-fourth that of Hong Kong.

Shenzhen became an expansion outlet for Hong Kong manufacturers and the timing could not have been better. The availability of abundant inexpensive land and labor in Shenzhen made it possible for Hong Kong manufacturers to move labor-intensive processes across the river.

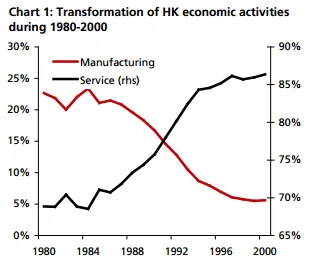

Meanwhile, more skill-intensive business activities such as R&D, marketing, and management continued to be performed in Hong Kong. Such division of labor had resulted in Hong Kong’s continuous prosperity and a significant transformation of economic activities. The manufacturing sector’s share in GDP decreased from 23% in 1980 to 6% in 2000, while that of the service sector’s increased from 69% to 86% (See chart 1).

Another trend is the increasing use of Hong Kong’s financial services by China. In addition to providing financial advices and consultation services, Hong Kong has become a center of fundraising for Chinese firms. Mainland-backed companies began raising capital in Hong Kong’s stock market through share placements in 1987. Also, the first Chinese enterprise listed its H shares in 1993. With the development of local-serving and internationally oriented banking services, Hong Kong has emerged to a global financial center just as New York, London, and Tokyo.

The cost problem has never subsided, however. In the past three years, Hong Kong has ranked the world’s most expensive office market. The situation will probably become more acute in the years ahead given the low rate of new office completions (See chart 2).

The stratospheric rental cost erodes the competiveness of today’s Hong Kong’s financial and other service industries, which takes up over 90% of GDP altogether. To trim operating costs, some companies are seeking to reconfigure their office footprints in Hong Kong.

This often takes the form of moving mid-to-back office functions to decentralized areas in order to free up more expensive space for front office services. However, suitable premises are difficult to source locally. Relocation thus becomes another option.

Singapore is often touted as an alternative to Hong Kong’s high rental prices and lack of supply. Rents are only close to half of Hong Kong’s and there is an abundance of high quality, grade-A space available (See chart 3).

But a significant movement from Hong Kong to Singapore has yet to be seen; in part due to the enviable location Hong Kong enjoys as a gateway to the mainland. 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 Chart 2: HK new office completions Sqm (k)0 200 400 600 800 1,000 1,200 Mar-00 Mar-03 Mar-06 Mar-09 Mar-12 Grade A, Central, HK Central area, SG HKD/sqm Chart 3: Office rental Latest: Jun 13

Qianhai, a 15 sq km district located on the western side of Shenzhen with just an hour’s drive from Hong Kong’s central business district (CBD), could be considered as a solution. The recent land auction of 14 million sq ft GFA (gross floor area) of commercial space, comparative to the existing grade-A office market in Hong Kong’s CBD, is a significant step in a scheme that could alleviate the severe shortage of Hong Kong’s office space.

In addition to land, Qianhai also offers relatively cheap human resources. In spite of the 30% growth in average wage over the past three years (compared with 20% in Hong Kong), labor cost in Shenzhen currently is still about half that of Hong Kong.

And thanks to the huge investment made on education by the government, the quality of Chinese labor has improved significantly in the past decade. In particular, the number of college graduates in Guangdong in 2012 has quadrupled the level seen in 2002.

Therefore, relocation to the zone allows firms in lowering operating costs as well as tapping the mainland growing pool of qualified labors.

Strengthens Hong Kong’s role

Apart from easing the physical problems faced by Hong Kong, another important task for Qianhai is to strengthen Hong Kong’s role as an offshore RMB centre. The aforementioned cross-border RMB loan scheme is a milestone in this regard.

The scheme provides Hong Kong banks a new attractive avenue for RMB fund investments; the growth of which has far been lagging behind that of other offshore RMB products. For instance, the total outstanding RMB loans in Hong Kong merely amounted to RMB88 bn, compared with the dim sum bond market’s RMB500 bn (See chart 4).

The limited size of RMB-settled business for Hong Kong companies is a major factor that attributes to the weak RMB loan growth, according to a survey constituted to the DBS RMB Index for VVinning Enterprises (DRIVE). Cross-border lending is thus essential in improving the demand and yield on the offshore RMB deposit; and subsequently the RMB circulation in Hong Kong.

On the other hand, the scheme provides a direct channel for Qianhai firms to access cheaper offshore RMB funding; thereby enhancing their operating margin. Small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), those who have long struggled to raise funds from the large state banks, see particular benefit. The smaller amounts accessible from Hong Kong banks with more established SME lending policies will be of greater value to them.

Besides loans, the scope of RMB business between two jurisdictions is set to be further expanded. In particular, the Qianhai Equity Trading Center will provide lending facilities to enterprises registered in the zone by launching RMB-denominated wealth management products in the Hong Kong capital market (see “CNH: Qianhai to offer CNH trust products”, 16 May 2013).

The authorities are also planning to allow Qianhai companies to directly issue dim sum bonds in Hong Kong. Furthermore, individual investors in the zone might be allowed to participate in the RMB-denominated version of Qualified Domestic Institutional Investor program (RQDII2). Chinese regulators have also reportedly given the green light for offshore companies to set up private equity funds in Qianhai. The capital market and financial institutions in Hong Kong should continue to benefit from such liberalization initiatives.

Dissimilarity

Despite the fact that the Qianhai program is a mimic of the Shenzhen SEZ model, the two are different in one aspect.

In 1980-90s, Hong Kong manufacturers were able to lower their operating costs successfully by moving northward. And their selling prices were kept high since the vast majority of products were exported to high-income countries (i.e., the US and Western Europe).

That was best demonstrated by the steady rise of the city’s export unit value during the period (Chart 5). The huge amount of inward investment in Shenzhen can also be seen as a result of the soaring profit margins. By 1994, Shenzhen had already utilized more FDI (USD5.35 bn) than the targeted amount set for 2000 (USD1.5 bn).

Today, however, exportation was no longer focused in the west. Much effort was put to selling within China. In 2012, 54% of Hong Kong’s exports were destined for the mainland, a tremendous increase from 6% in 1980; whilst exports to advanced economies have fallen to 32% from 71% (See chart 6).

Arguably, China is now one of the most hypercompetitive markets in the world. Market penetration has been a major challenge for non-Chinese enterprises. Experience shows that foreign brands always have to embark on price cutting strategies in bid to gain market share amid fierce competition. This happened to Starbucks, Wal-Mart, IKEA, and many other newcomers in the mainland service industry.

In other words, the opportunity arises from today’s Qianhai initiative is less obvious than that offered to Hong Kong manufacturers three decades ago.

Against this backdrop, favorable taxation policies would be crucial in incentivizing Hong Kong enterprises to establish their presence in the zone. Currently, the corporate tax rate in China is as high as 25%; compared with 16.5% in Hong Kong. Imitating Hong Kong’s low tax rate system might be a plausible option.

Indeed, a low-tax initiative is already taken place in attracting foreign workers. The government has recently capped the individual income tax (IIT) rate for expats working in the zone at 15%; on par with Hong Kong. Such tax break makes Qianhai stands out from the rest of the country, where the IIT rate could be as high as 45%.

While the tax incentive would facilitate the flow of talent across the border, there is nevertheless a widespread view that the pool of Hong Kong’s professionals will be adversely affected. Yet, there is little evidence of the extent to which local workers are harmed by relocation.

In the 80s, the increase in the emplo

yment of skilled workers in Hong Kong was accompanied by an increase in their relative wages (See chart 7). This was characterized by the fact that although labor-intensive industries relocated productions to Shenzhen, technology- and knowledge-intensive functions remained anchored in Hong Kong.

Moreover, the manufacturers that stayed in Hong Kong started moving away from low-end production into high value-added products that could compete internationally. That, as a result, has generated increasing demand for skilled workers in Hong Kong.

Likewise, it is expected that certain mid-to-back office functions will relocate to Qianhai for lower operating cost. But the headquarters are likely to remain in Hong Kong due to reasons ranging from the availability of skilled and experienced executives to the well-established legal system.

In addition, the expansion of RMB flows channel through Qianhai would create new job openings in Hong Kong, such as those for RMB lending and dim sum bond issuance. In sum, Qianhai and Hong Kong would both benefit and share the rise in job opportunities in accordance to their relative advantages.

Conclusion

The experience in 80s has proven that the high level of complementarity in factor endowment led to dynamic economies of scale that are mutually beneficial. Hence, the rise of Qianhai today should not be considered a zero-sum game. Given its geographical proximity, Qianhai provides a unique platform for Hong Kong’s enterprises to overcome regional and systemic barriers; thereby increasing their presence in Shenzhen.

As such, collaboration between Hong Kong and the whole Pearl River Delta could be further enhanced. Meanwhile, as an experimental area of modern service industry, Qianhai will provide valuable references for the nation, in which the service sector is playing an increasingly important role.

On financial development, Hong Kong will benefit from the rise of RMB business with the establishment of Qianhai as a test bed for RMB internationalization. The Qianhai’s success, on the other hand, will produce a demonstration effect in exploring the path for capital account liberalization in China.

Advertise

Advertise