What you must know about CNH's onshore deregulation and offshore expansion

By Nathan Chow Hung Lai (周洪禮)The Shanghai Free Trade Zone (SFTZ) opened on 29 Sep.

According to the blueprint, financial innovations including RMB convertibility and interest rate liberalization are the priorities on the reform agenda (see “Shanghai Free Trade Zone & the reinvigoration of

However, some worry that the establishment of SFTZ will undermine the development of offshore RMB markets. Such fear is unwarranted. Looking at the Eurodollar market could help shed light on how offshore market grows in spite of onshore deregulation.

Experience from the Eurodollar market

During the 1960s, changes in US regulations such as reserve requirements, interest rate restrictions, and borrowing limits made offshore banking more attractive to local banks. Consequently, USD liquidity migrated to

In the late-1980s and early-90s, most of the aforementioned regulations were eliminated.

For instance, the Federal Reserve lowered reserve requirements on large-denomination domestic deposits to zero; in effect removing that ‘tax’ on local intermediation. But the Eurodollar share of global dollar banking had grown from 10% in 70s to 20% in 90s and over 30% in mid-2000s.

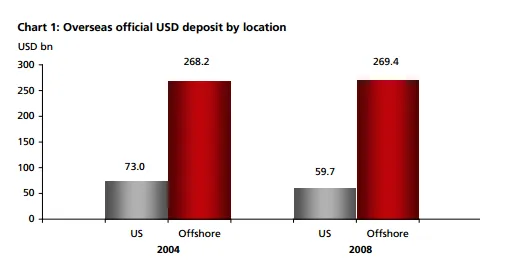

Non-US residents continued to hold the majority of their dollar offshore, and so did the official holders of dollar reserve (mostly overseas central banks). During the 2000s, more than 70% of official dollar reserves was placed outside the

The sustainable growth of the Eurodollar market can be attributed to a number of factors. Most characteristically, it has served as an efficient intermediary between non-US lenders and non-US borrowers of dollars (also known as third-party intermediation).

For example, the central bank of UAE deposits USD10 mn in a London bank, which then lends the funds to a Mexican oil importer.

In this case, the dollars might go through one or more offshore interbank transactions that could take place in

But it does not require either sourcing funds or deploying funds in the

As of Jun10, of the USD4.9 trn total claims booked offshore, USD2.7 trn (or 55%) were claims on non-US residents (Chart 2). Convenience factors such as regulatory environment, accounting standards, and time zone difference might explain the market participants’ preferences for offshore transactions.

Another motive is to separate currency risk from country risk. In September 2001, for instance, the trading of US Treasury securities was interrupted due to terrorist attacks.

But overseas central banks with dollar securities held in European depositories were still able to carry out normal operations. That reminds official reserve managers the potential benefits of having diverse trading and custodial locations.

Other factors contributed, too. Volumes of literature have pointed to the Soviet Union’s placement of dollar deposits in

Implications for offshore RMB markets

Judging from the dollar experience, global investors prefer to transact in a particular currency through the offshore markets. With respect to the RMB, the offshore market in

Specifically, there is always a demand for separating currency risk from country risk amid concerns over concentration of infrastructure or operational risk in one jurisdiction.

This is especially so in

This suggests the municipality has yet to become a world-class city in terms of business activity, human capital, information exchange, and cultural experience.

Foreign investors are also highly sensitive to changes of political atmosphere in the mainland, which is in transition towards a market economy amid fierce resistance from vested interest group. Any severe domestic volatility has the potential to force sweeping governmental actions; including financial reform.

Against this backdrop, investors need alternative venues to diversify their RMB exposures. The growing appetite for dim sum bonds of overseas institutional investors (including central banks), some of whom already have access to the mainland bond market (through QFII scheme), can be seen as a result of such risk-diversification behavior.

Dim sum bonds, notably, are being issued by not only mainland entities but also multilateral companies as well as international institutions, such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

This underscores the fact that the offshore RMB market is, to an increasing extent, functioning as a platform for RMB financial activities conducted among non-Chinese residents. Renault, a French automaker, sold a three-year dim sum bond earlier this year, 45% of which were taken up investors outside of

Meanwhile, banks in

Such rapid growth of financing activities are the result of several encouraging policies, including allowing non-residents to borrow RMB (see “CNH: More than just “non-resident conversion”, 13 Aug 2012) and liberalizing banks’ RMB net open positions and statutory liquidity requirement.

The Treasury Markets Association also introduced CNH HIBOR fixing recently. This provides a benchmark to price loan facilities and facilitates the development of offshore RMB interest rate swap market. As the market deepens and a greater variety of RMB products become available, more RMB intermediation within the offshore markets will be seen.

Adding to that is the less consistent appreciation expectation of the RMB. Non-resident borrowing in the RMB going forward will be less discouraged by the previous one-way expectations on the exchange rate.

Other offshore RMB centers also possess respective long term edges.

For instance, an Indonesian mining company may settle its trade with a Malaysian customer in RMB as long as doing so enables them to lower transaction costs or manage currency risks better. In 2012, ASEAN surpassed

The RMB liquidity generated from trade flow, alongside the RMB acquired from swap lines signed with

Likewise,

Conclusion

Historical experience has shown that onshore deregulation did not interrupt the growth of the offshore markets. Non-US residents, private and official alike, reveal strong preference for doing dollar business in the Eurodollar market. Such behavior prevailed even after

Third-party intermediation has since become the norm for the Eurodollar market. An inference is that the offshore RMB markets will increasingly play a similar role of intermediating among non-Chinese residents. The benefit of such positioning can persist in the long term, even when the RMB becomes convertible.

Advertise

Advertise